Petroglyphs, mirror of the peoples of Central Asia

Long neglected by scientists, the study of rock art represents a direct gateway to the imagination of peoples who have lived across the vast natural expanses of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan.

Samuel Maret

The first artistic events

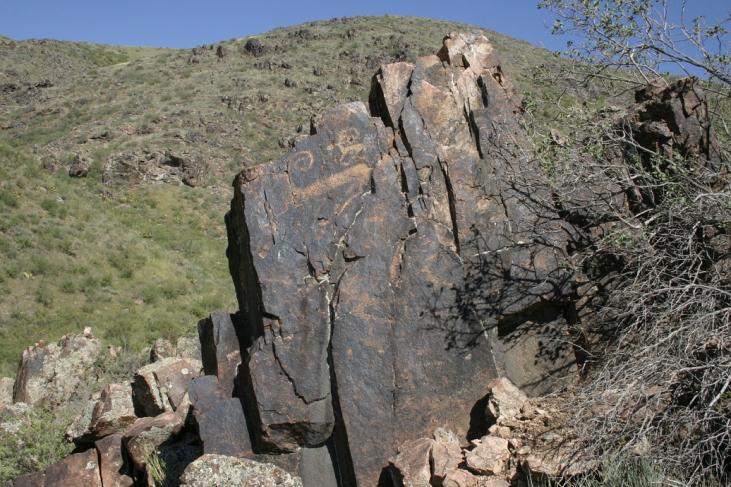

The earliest artistic manifestations in Central Asia consisted of designs called petroglyphs made by picketing on rocks in the open air. This so-called rock art should not be confused with the cave art of the caves of France and Spain. Cave art developed in the Paleolithic period, between 40,000 and 10,000 BC, at a time when man lived solely on hunting and gathering, in a cold climate. Rock art, on the other hand, appeared over almost the entire surface of the earth around 3000 BC after humans mastered animal domestication and grain cultivation.

These open-air designs have developed on all continents. In Asia, these petroglyphs are found in an exceptionally important way in Siberia, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Recent scientific research in Central Asia

The first records of rock art in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan appear in the middle of the 19th century following scientific expeditions. However, since the drawings discovered could not be attributed chronologically, no specific study or research was undertaken.

It was not until the 20th century that archaeologists became interested in the petroglyphs of Central Asia, in particular thanks to the discovery of Saimaluu-Tash in Kyrgyzstan in 1902. The documentation of the site did not begin until 1946, however, creating an emulation with archaeologists to search for new sites. Thus, in 1956, VM Gaponenko discovered Zhaltyrak-Tash in the region of Talas in Kyrgyzstan, while Anna Maksimova revealed the now famous site of Tamgaly in Kazakhstan in 1957. New research was carried out in the early 1970s, notably by AN Maryashev in Kazakhstan, discovering Eshkiolmes and BayanZhurek, and by GA Pomaskina, listing for the first time the sites around Lake Issyk-Kul.

This site is recognized by UNESCO

Following the collapse of the Soviet bloc, European archaeologists come to support their Kazakh colleagues under the direction of A. E. Rogozhinsky to participate in the documentation of Tamgaly. In 2004, this site was recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Since this recognition, archaeologists have been faced with the need to systematically and comprehensively document the sites discovered, and no longer, as previously, to provide only photos of a few important panels. Thus, for the past ten years or so, the sites have been explored again in a methodical manner, allowing the discovery of new major sites, such as that of Kulzhabasy, as well as new petroglyphs, in particular at Tamgaly. Unfortunately, the publication of the results is still too partial or even absent, thus preventing UNESCO from being able to recognize important sites such as those of Saimaluu-Tash in Kyrgyzstan or Eshkiolmes in Kazakhstan.

Drawings linked to the natural context

In Kazakhstan, the main sites are located in the oblys of Almaty (Tamgaly, Bayan Zhurek, Eshkiolmes), Djamboul (Akkainar and Kulzhabasy) and southern Kazakhstan (Arpa-Uzen), although petroglyphs are found in others. oblys, especially around Baikonour. The sites are located in semi-mountainous valleys opening onto the steppes, between 1000 and 1500 m altitude. These places offered both a water supply in the summer, as well as shelter from the wind in the winter, with sufficient pasture throughout the year.

In Kyrgyzstan, rock art is concentrated in the regions of Talas (Zhaltyrak-Tash), Naryn and Jalal-Abad (Saimaluu-Tash) and Issyk-Kul, mainly on the north shore of the lake (Ornok, Baet, Kara-Oï, Tcholpon-Ata). While many publications have been published on the Soulaiman-Too petroglyphs in Osh, these are in reality of no particular interest due to their limited number and the impossibility of relating them to a specific cultural tradition. Their promotion was linked more to the political will to assert the city's past. Moreover, there is nothing to confirm that these drawings were well executed 3000 years ago.

Rock art is part of its environmental context. Due to the geomorphology of Central Asia, grazing grounds are dotted with rocks, moraines and cliffs, covered with a black patina. By hitting these stones with another stone or a metal object, a lighter surface appears under the patina, allowing drawings to be made. These are revealed by the play of natural light. In addition, they are part of a route due to the cliffs and fields of moraines and in a contextualization by the voluntary proximity of certain panels.

From the Bronze Age to Lenin, the mirror of a mental universe

The first petroglyphs in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan were probably made during the Bronze Age, between 2000 and 1000 BC. Men are sedentary and practice agriculture and animal husbandry. They move aloft with their herds in the summer and descend into the valleys in the fall. The men of this time will therefore represent their mental universe, that is to say what marks them and influences them in their environment and in their religious and social practices. Therefore appear on the rocks of the bulls, goats, horses, camels and deer, wolves, snakes, carts and plows, as well as solar deities (man-sun, sometimes accompanied by humans in a state of worship, arms raised to the sky).

The two great cults of this time are those of the sun and the bull. These two cults are contradictory and complementary: the bull, a black animal, symbolizes bestiality and darkness and therefore faces the sun, personalized by an anthropomorphic figure.

The third great cult is that of virility, in particular through sexual scenes or battle scenes. The main sites of this time are those of Saimaluu-Tash, Tamgaly, Kulzhabasy, Eshkiolmes and Akkainar.

The Iron Age succeeded the Bronze Age, between 800 and 300 BC, with several changes, ethnically, socially and culturally. The Scythian people, originally from Altai, invade Central Asia. Although still practicing herding, men are however much more nomadic than in the Bronze Age. They continue to represent their mental world on the rocks, with consequent thematic and stylistic differences compared to the Bronze Age: disappearance of representations of bulls, sun-men, wagons and plows, over-representation of goats and goats. hunting scenes. At the beginning of the period, the drawings were sometimes marked by an excessive naturalism, with almost life-size representations of deer and goats. In addition, the style is sometimes marked by curves and volutes. At the end of the period, the theme and style were oversimplified: the animal depicted became almost exclusively a caprine and was only depicted in a few lines. The main sites are located on the north shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, as well as at Zhaltyrak-Tash.

The tradition of petroglyphs was revived with the emergence of Turkish peoples in the early Middle Ages (between AD 700 and 1200). These peoples renovate the old petroglyphs, complete them and bring some novelties, with riders carrying banners, caravans of camels and especially many riders riding camels. The style is naturalistic and the main sites of this period are in Baet, on the north shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, as well as in Akkainar.

Finally, the tradition of rock art in Kyrgyzstan is carried on by the shepherds of our time. Having to watch their herds, they "kill" time by continuing to represent on the stones what marks them in their environment, whether it is the appearance of cars or the cult of Lenin in Soviet times. These drawings are mainly located on the north shore of Lake Issyk-Kul and in Kulzhabasy.

A past doomed to disappear?

With urban development, several sites, especially on the north shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, are threatened. Thus, in Baet, several fields of moraines were "cleaned" in order to facilitate farming. In Kara-Oï, a storm basin was built among the rock art area. In addition, the air pollution generated by road traffic attacks the patina of the stones, accelerating the frostbite, that is to say the bursting of the engraved surface.

Finally, the accelerated tourist development, with visitors climbing the rocks or engraving their names on millennial drawings shows how the rock art of Central Asia is strongly threatened, even doomed to disappear in the medium term, if no awareness of the population and politicians is conducted. However, this art is essential for understanding the history of the region, while protecting sites with a real welcome for tourists would enhance the attractiveness of Central Asia as a destination for travelers from all over the world.

However, this art only takes on its meaning in its environmental context. We should therefore not want to move the main panels to museums. Certainly, the design could be admired, but without nature and the relation to other petroglyphs, it would lose its intrinsic meaning, its archaeological value and its true beauty.

Author Luc Hermann (article published by Novastan.org)

Archaeologist (University of Liège). Author of numerous scientific articles on rock art in Central Asia and of six books.